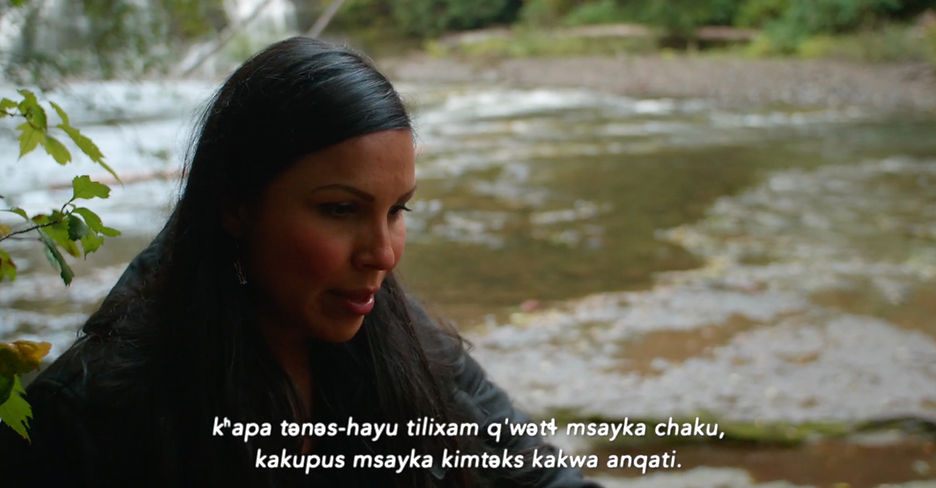

Still from małni — towards the ocean, towards the shore (2020).

małni — towards the ocean, towards the shore: A Perspective of an Indigenous Nation from Sky Hopinka

By DOAK DEAN

In the film małni — towards the ocean, towards the shore (2020),[1] we meet two members of the Chinook Nation in Oregon and Washington: Sweetwater Sahme and Jordan Mercier. The film opens with the vast natural landscape of the Pacific Northwest and the resonant sounds of the Chinook Wawa language. While the narrator and filmmaker, Sky Hopinka, begins the voiceover, it’s not long before the viewer hears Sweetwater and Jordan. As their voices grow more present, so too does the viewer’s insight into Chinook culture. Sweetwater reflects on personal distance and reconnection with her cultural roots, while Jordan speaks about the Chinookan death myth and his evolving relationship with his heritage. Their journeys are intimate, evolving interpretations of their past, present, and future within the Chinookan cosmology.

małni — towards the ocean, towards the shore cannot be put in a box. It investigates the Chinookan death myth, but it uses many non-traditional methods to explore this narrative. First and foremost, Sky Hopinka narrates the film in the Chinook Wawa language. By deciding to make Chinook Wawa the first thing the viewer hears and the film’s primary narration language, Hopinka immediately rejects the typical voyeuristic style that Western documentaries often adopt when depicting marginalized communities. While many Western documentaries film native languages, and simply translate it for ease of understanding, Hopinka strays from this. He represents the Chinook Wawa language in narration or subtitles throughout the entirety of the film. When someone speaks English, there are Chinook Wawa subtitles. When someone speaks Chinook Wawa, there are English subtitles. Although Hopinka does translate the language to some degree, he makes sure not to abandon the Chinook Wawa language in the moments of English speaking. This constant use of Chinook Wawa–in subtitles or audible fashion–helps avoid a hierarchical structure to the languages used in the film. Chinook Wawa is just as prevalent as English, if not more. Hopinka turns the common trope of translating native languages into subtitles on its head. This allows the viewer to sit with the language and encourages them to understand it. While most Western documentaries might briefly use the language as a gimmick to “show” the culture they are misrepresenting, Hopinka doesn’t sacrifice a vital part of Chinook culture for the possibility his film is more easily understood. Hopinka also creates a barrier by using this language. Rather than creating accessibility for someone unfamiliar with Chinookan culture, he does the opposite. If the viewer doesn’t speak Chinook Wawa, they are reliant on subtitles to understand what is being communicated during the film’s narration in Chinook Wawa. This creates a sense of power for the Chinook Wawa language and for the people who speak it while watching the film.

.jpg)

The decision to place Chinook Wawa at center stage is inherently a political statement: Indigenous languages are not gone or forgotten, but rather alive and still evolving. They are not secondary to widely spoken languages. Instead, they are cultural mechanisms for maintaining power over their respective nations' individuality and autonomy. Chinook Wawa is a part of the Chinookan people and, in part, makes them who they are. The language cannot simply be replaced with an audible translation, because hearing and speaking it is an essential part of the language’s experience. Sky Hopinka commented on this idea in a 2021 interview with Space Gallery, saying, “Language became a means of conveying their [Jordan and Sweetwater’s] stories and their voices, and I wanted to do as little as I could to get in their way.”[2] By intentionally using Chinook Wawa, he adds authenticity to the film's experience at the expense of accessibility. Not speaking the language puts the viewer in a place of vulnerability and encourages them to encounter the experience of Chinookan people and their language without dissecting or controlling it.

The use of Chinook Wawa in małni does more than just challenge Western film practices and their tendency to dismiss cultural pillars in favor of more easily digestible content — it also plays a significant role in the film’s structure. Hopinka uses the language to create a poetic and immersive quality. The Chinook Wawa narration brings a rhythm and tone to the film that no other language could replicate. Chinook Wawa has a slow cadence, with long pauses between statements. It flows poetically and reflects a dreamlike state. This cadence is mirrored in the film. Hopinka uses many long takes and slow pans that work in congruence with his narration.

An example of this occurs from minute 26:00 to 27:10 in the film. The camera circles a comet structure at the museum. It is a slow and continuous pan, and the narration comes in separated, calculated bursts that give a dreamlike quality to the scene.

Throughout the film, the visuals and Chinook Wawa narration work together to develop a poetic rhythm that anchors the pacing. The language also structures the film through the intentional lack of subtitles at certain points. This occasional withholding of information keeps the viewer in an ambiguous state. When they don’t know how to exactly interpret the scene, it reinforces the film’s experiential nature. The viewer is reminded that Hopinka doesn’t intend to explain Chinookan culture. Instead, he aims to offer an experience. He draws the audience in by giving them some information, but not enough to come to a conclusion he has predetermined. In Hopinka’s interview with Hyperallergic, he described that he wanted to make a film that people could experience and not necessarily understand [3]. This doesn’t mean that Chinook Wawa is the only tool he used to accomplish this effect. Rather, it offers insight into Hopinka’s reasoning behind omitting the clarity that some translations might provide, in favor of experience.

Still from małni — towards the ocean, towards the shore (2020).

Throughout the film, the visuals and Chinook Wawa narration work together to develop a poetic rhythm that anchors the pacing. The language also structures the film through the intentional lack of subtitles at certain points. This occasional withholding of information keeps the viewer in an ambiguous state. When they don’t know how to exactly interpret the scene, it reinforces the film’s experiential nature. The viewer is reminded that Hopinka doesn’t intend to explain Chinookan culture. Instead, he aims to offer an experience. He draws the audience in by giving them some information, but not enough to come to a conclusion he has predetermined. In Hopinka’s interview with Hyperallergic, he described that he wanted to make a film that people could experience and not necessarily understand [3]. This doesn’t mean that Chinook Wawa is the only tool he used to accomplish this effect. Rather, it offers insight into Hopinka’s reasoning behind omitting the clarity that some translations might provide, in favor of experience.

Like the heavy influence Chinook Wawa has on the film structure, the Chinookan death myth helps guide the film as well. As the viewer watches the film, they learn that the death myth is a central pillar in Chinookan culture. The death myth is cyclical and non-linear in nature. It reveals life and death are less binary than they might seem. A person’s death is not an end, but rather a transition into a different form of life. The film reflects this idea in its structure and narrative. Hopinka makes a conscious choice to jump from character to character in cyclical fashion. As this cycle occurs, Hopinka also jumps back and forth in time, and he cuts between scenes showing land and water. Throughout this process, the viewer comes to understand the film as a representation of the Chinookan death myth. It is not life or death, but rather where one is in the cycle of existence.

Although Hopinka uses this sacred cultural pillar as a theme in the film, he does so in a non-traditional way. Like his use of language, he avoids the typical voyeuristic style of Western documentaries. One example is the scene toward the end of the film when Jordan Mercier is praying by a waterfall. While most documentaries would show his prayer to the viewer, Hopinka elects to blur the frame and spin in a circle for a long duration. This allows the viewer to sit with the prayer while not exoticising it. He allows privacy and respect to Jordan’s prayer, and therefore his culture. Hopinka’s desire to make the film an authentic perspective is very clear in this portion of the film. He does not attempt to simplify Chinookan culture at the expense of easy understanding.

Overall, małni — towards the ocean, towards the shore allows viewers to have an immersive experience with Indigenous culture. The filmmaker, Sky Hopinka, portrays Chinookan culture in a non-voyeuristic way by allowing the Chinook wawa language and the death myth to inform the film’s structure. Instead of creating a film that is easily digestible for someone removed from Chinookan culture, he constructs a challenging piece that empowers the community it portrays. It demands that the viewer let go of their urge to categorize or fully understand the culture, instead highlighting the unique qualities of the Chinookan language, death myth, and overall experience. At its core, małni sacrifices many popular cinematic conventions to protect Chinookan culture from being simplified in favor of entertainment. Hopinka’s creation is a powerful resistance to filmmaking practices that have exoticized or minimized marginalized communities for far too long.

REFERENCES

[1] Hopinka, Sky, dir. małni — towards the ocean, towards the shore (2020).

[2] Hopinka, Sky. “Interview with Sky Hopinka” Interview by Dan Hawkins & Greg Jamie. SPACE Reader, April 20, 2021. https://space538.org/reader/interview-with-sky-hopinka/

[3] Hopinka, Sky. “Sky Hopinka Is Tired of Explaining Everything to Non-natives” Interview by Erin Joyce. Hyperallergic, February 6, 2023. https://hyperallergic.com/798442/sky-hopinka-is-tired-of-explaining-everything-to-non-natives